This temporary spotlight display opens on February 22nd and runs until April 22nd. It includes a selection of objects, artworks and poetry from the 18th century to the present to explore the legacy of the Haitian Revolution and its leader Toussaint Louverture.

I cannot recall when exactly I learned the revolutionary leader Toussaint Bréda had added Louverture to his name, declaring himself the opening. Undeniably, he was an avant-garde of Black freedom, and events in Haiti would turn into a contagion spreading throughout the hemisphere and beyond, eventually transforming parts of the world. He dared to proclaim himself Louverture, a striking act of Black self-determination that would give birth to a Republic. A rebel’s spirit. Kindred.

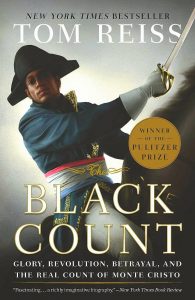

John Kay (1742–1826), Toussaint Louverture in A Complete Collection of the Portraits and caricatures Drawn and Engraved by John Kay Edinburgh From the year 1784 to 1813. Etching, 1802.

As both an artist and anthropologist, I remain curious about the motivation and potential of this exhibition in the current, racially charged, global political moment. Living in the United States, the invitation to offer a response to the Asahi Shimbun Display A revolutionary legacy: Haiti and Toussaint Louverture has significance beyond the massive walls of the British Museum. In the 21st century, Black humanity is still in question. Black lives are still of less value and continue to be under siege everywhere. Haiti’s plight, and the exploitation of Haitians, is part of the current news cycle in the UK at the time of writing this. Moreover, the legacies of slavery often sanitised to the past outside of academic circles, continue to unfold in our daily lives.

For some years now, I have been working on how to express, give voice to, and textually represent, Black struggle, rage and liberation, informed by the late Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot. In his book Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, he asserted that, ‘none of us starts with a clean slate. But the historicity of the human condition also requires that practices of power and domination be renewed.’ According to Trouillot, we are, ‘caught in legacies of past horrors that are made possible only by their renewal.’

How does one react, create and meditate on subjugation, defiance, triumphs and re-subjugation when the past is now, when the past has become our present? Can such a creative performance be an intervention, an opening?

Only a remix will do, for performing this revolution will be live. After total immersion in my research process with the usual scholarly suspects, I have to admit that I have been actively excavating ghosts. Inspired by reawakened Ancestors. As feminist scholar M Jacqui Alexander has so eloquently noted in her book, Pedagogies of Crossing, ‘the dead do not like to be forgotten.’

The question that looms largest and grounds my work is a simple one: a revolution against what? Haiti is symbolic of Blackness globally. Colonial tactics in the Caribbean region were put into practice elsewhere. My task is to put interconnected histories of colonialism, slavery and rebellion in concert with more contemporary musings on freedom, from Suzanne Césaire and Frantz Fanon, to James Baldwin, Billie Holiday and Nina Simone, among others. I want to viscerally contemplate the unfinished business of a Black Revolution, which achieved what none of the preceding European revolutions, with their investment in enslavement, could: universal freedom for all races. An opening.

Perhaps no other place than the British Museum would be as fitting a site for this date with history. Historical amnesia may have effaced Britain’s role in Haiti’s revolutionary struggles, but we are still connected. Carrying out research at the British Museum, an imperial lakou (the Haitian Kreyòl word for yard, compound) with its origin and immense holdings, demanded I confront Empire as an outsider peering in. Every corner of the Museum was arresting in its own way. A living, breathing monument that has too many stories to tell. The Enlightenment Gallery (Room 1) with Sir Hans Sloane’s natural and artificial rarities made me curiouser and curiouser. The great Reading Room, where Karl Marx worked on Das Kapital, reminded me that the Communist Manifesto was recently translated into Kreyòl. The Money Gallery (Room 68) was a potent reminder that during the US Occupation of Haiti (1915–1934), Haiti’s gold reserves were confiscated by the Marines and brought to the vaults of the National City Bank of New York. Curiouser and curiouser. William Wordsworth’s sonnet To Toussaint L’Ouverture (1802) and John Agard’s response are also raw material for me.

Vodou boula drum of the Rada battery, seized during the US occupation of Haiti. Early 20th century.

Two objects continue to linger in my mind: a little boula drum, especially well cared for by the conservators, and the Akan drum, evidence of the transatlantic slave trade that, dare I say, belongs on a pedestal?

Akan drum. Made in West Africa and collected in the American colony of Virginia probably between 1710 and 1745.

Drums are instruments attuned to spirits. The 37 steps down to the African Galleries (Room 25) where the Benin bronze sculptures are on display got me wondering how they made the crossing after the 1897 Punitive Expedition. Bodies had been strewn across the depths of the Atlantic for centuries.

I felt a profound longing for cowries.

So I will bring my chants along with a textual rasanblaj (the Kreyòl word for gathering) — a remix of things that have been said or sung many times. I have nothing to disclose that has not been heard before. Will anything I say be remembered? As Ms Lauryn Hill sangwith The Fugees, ‘Ready or not, here I come, you can’t hide. I’m gonna find you and take it slowly…’

The Asahi Shimbun Display A revolutionary legacy: Haiti and Toussaint Louverture, supported by The Asahi Shimbun, is in Room 3 until 22 April 2018. Gina Athena Ulysse will perform her new piece in the Stevenson Lecture Theatre at 18.30 on Friday 16 March.

Source: British Museum