Introduction

Napoleon is widely seen as a military genius and perhaps the most illustrious leader in world history. Of the 60 battles, Napoleon only lost seven (even these were lost in the final phase). The leading British historian Andrew Roberts, in his 926 pages biography Napoleon: A Life (2015), mentions the battles of Acre (1799), Aspern-Essling (1809), Leipzig (1813), La Rothière (1814), Laon (1814), Arcis-sur-Aube (1814), and Waterloo (1815). Often forgotten is the battle that Napoleon lost in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). On 18 November 1803, the French army under the command of general Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau, and the rebel forces under Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a self-educated slave with no formal military training, collided at the battle of Vertières. The outcome was that Napoleon was driven out of Saint-Domingue and Dessalines led his country to independence. It is interesting to see what Napoleon’s legacy was.

Saint-Domingue’s sugar

Saint-Domingue was a French colony on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola from 1659 to 1804. The French had established themselves on the western portion of the islands of Hispaniola and Tortuga by 1659. The Treaty of Rijswijk (1697) formally ceded the western third of Hispaniola from Spain to France. The French then renamed it to Saint-Domingue. During the 18th century, the colony became France’s most lucrative New World possession. It exported sugar, coffee, cacao, indigo, and cotton, generated by an enslaved labor force. Around 1780 the majority of France’s investments were made in Saint-Domingue. In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue grew to be the richest sugar colony in the Caribbean.

Revolution in France

A plantation in the Caribbean was very labor intensive. It required about two or three slaves per hectare. Due to the importation of Africans the slave population soon outnumbered the free population. The slave population stood at 460,000 people, which was not only the largest of any island but represented close to half of the one million slaves then being held in all the Caribbean colonies (Klein: 33).

Conditions on sugar plantations were harsh. During the eight-month sugar harvest, slaves often worked continuously around the clock. Accidents caused by long hours and primitive machinery were horrible. In the big plantations, the slaves lived in barracks. Planters primarily wanted males for plantation work. There were few women as these were only needed for propagation. Families did not exist. The result was a kind of rebelliousness among the slaves which manifested itself in various ways. Planters reported revolts, poisonings, suicides, and other obstructive behavior. These men, women and children did not have a life or history of their own.

Slavery was ultimately abolished in all French colonies in 1848 by Victor Schœlcher, the famous French journalist and politician who was France’s greatest advocate of ending slavery. On 10 May 2001, the French Parliament adopted Law 2001-434, of which the first article reads: “The French Republic acknowledges that the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trade on the one hand and slavery on the other, perpetrated from the fifteenth century in the Americas, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean and in Europe against African, Amerindian, Malagasy and Indian peoples constitute a crime against humanity.”

The start of the French Revolution in 1789 was the initiator of the Haitian Revolution of 1791. When the slaves first rebelled in August of 1791 they were not asking for emancipation, but only an additional day each week to cultivate their garden plots.

The French Revolution began in 1789 as a popular movement to reform the rule of Louis XVI. However, the movement became out of control and between 5 September 1793 and 27 July 1794 France was in the grip of a Reign of Terror. This period ended with the death of Robespierre. In the aftermath of the coup, the Committee of Public Safety lost its authority, the prisons were emptied, and the French Revolution became decidedly less radical. In October 1795, the National Convention (the third government of the French Revolution) used Napoleon Bonaparte and the army to crush riots. During the night of 4 October, over 300 royalist rebels were shot dead in front of the Church of Saint Roch. The rest had scattered and fled. Under the Directory that followed between 1795 and 1799 bourgeois values, corruption, and military failure returned. In 1799, the Directory was overthrown in a military coup led by Napoleon, who ruled France as First Consul and after 1804 as Emperor of the French.

Napoleon’s attitude towards slavery

In 1794, during the Terror period of the French Revolution, slavery in France’s colonies was abolished. However, this policy was not fully implemented. When unrest broke out in Saint-Domingue, Napoleon wanted to renew France’ commitment to emancipation, mainly because of political reasons. Napoleon stated that slavery had not been formally abolished, since the abolition had not been realized. His politics aimed at the return of the former French colonists. Napoleon believed they were better able to defend French interests against the British that the revolutionaries. Thus as First Consul, by a decree of May 20, 1802, Napoleon restored slavery and the slave trade in Martinique and other West Indian colonies. The law did not apply to Guadeloupe, Guyane or Saint-Domingue:

AU NOM DU PEUPLE FRANÇAIS, BONAPARTE, premier Consul, PROCLAME loi de la République le décret suivant, rendu par le Corps législatif le 30 floréal an X, conformément à la proposition faite par le Gouvernement le 27 dudit mois, communiquée au Tribunat le même jour.

DÉCRET.

ART. I.er – Dans les colonies restituées à la France en exécution du traité d’Amiens, du 6 germinal an X [March 27, 1802], l’esclavage sera maintenu conformément aux lois et réglemens antérieurs à 1789.

Le décret du 30 floréal An X [May 20, 1802]

ART. II. – Il en sera de même dans les autres colonies françaises au-delà du Cap de Bonne-Espérance.

ART. III. – La traite des noirs et leur importation dans lesdites colonies, auront lieu, conformément aux lois et réglemens existans avant ladite époque de 1789.

ART. IV. – Nonobstant toutes lois antérieures, le régime des colonies est soumis, pendant dix ans, aux réglemens qui seront faits par le Gouvernement.

Although Napoleon did not believe in the idea of racial equality, later in his life, his attitude towards the African slaves became more ethical. His change of attitude is reveled during his exile on St. Helena. During that time, Napoleon developed a friendship with an old slave called Toby. When Napoleon heard how Toby had been captured and enslaved, he reportedly expressed a wish to purchase him and send him back to his home country. His loyal friend, the French atlas maker and author Emmanuel-Augustin-Dieudonné-Joseph, comte de Las Cases (1766 – 1842) notes in his well-known memoirs:

Napoleon’s kindness of heart was also shown by his attitude toward the Malay slave, named Toby, who had care of the beautiful garden at The Briars. When no one was in it the garden was kept locked and the key was left in Toby’s hands. Toby and Napoleon speedily became friends, and the black man always spoke of the Emperor as “that good man, Bony.” He always placed the key of the garden where Napoleon could reach it under the wicket. The black man was original and entertaining, and so autocratic that no one at The Briars ever disputed his authority. His story was rather pathetic.

Las Cases 1823: 217

and:

What, after all, is this poor human machine? There is not one whose exterior form is like another, or whose internal organization resembles the rest. And it is by disregarding this truth that we are led to the commission of so many errors. Had Toby been a Brutus, he would have put himself to death; if an Aesop he would now, perhaps, have been the Governor’s adviser, if an ardent and zealous Christian, he would have borne his chains in the sight of God and blessed them. As for poor Toby, he endures his misfortunes very quietly: he stoops to his work and spends his days in innocent tranquility…. Certainly there is a wide step from poor Toby to a King Richard. And yet, the crime is not the less atrocious, for this man, after all, had his family, his happiness, and his liberty; and it was a horrible act of cruelty to bring him here to languish in the fetters of slavery.

Las Cases 1823: 383

Napoleon’s war in Saint-Domingue

Napoleon had an obvious personal relation with the colonies. In January 1796, Napoléon Bonaparte proposed to Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie and they married on 9 March 1796. She adopted the name “Josephine” that Napoleon had chosen for her. Josephine was born in Les Trois-Îlets, Martinique. She was a member of a wealthy white planters family that owned a sugarcane plantation, called Trois-Îlets. Josephine was the eldest daughter of Joseph-Gaspard Tascher (1735–1790), knight, Seigneur de la Pagerie, lieutenant of Troupes de Marine, and his wife, Rose-Claire des Vergers de Sannois (1736–1807). The latter’s maternal grandfather, Anthony Brown, may have been Irish. It cannot have been a coincidence that slavery was specifically re-established in Martinique.

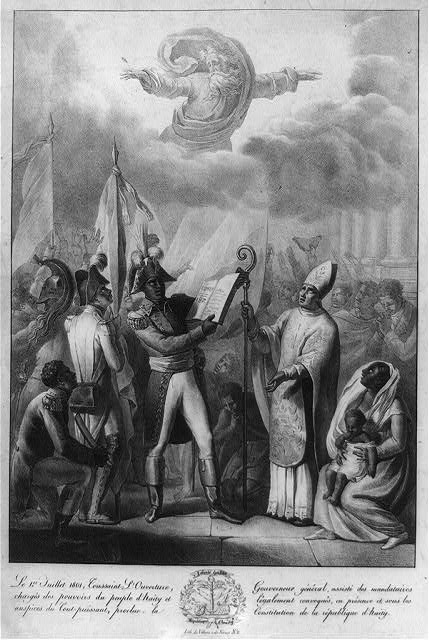

In 1791, the slaves and some free people of color in Saint-Domingue started a rebellion against French authority. In May 1791 the French revolutionary government granted citizenship to the wealthier mostly light-skinned free persons of color, the offspring of white French men and African women. Saint-Domingue’s European population however disregarded the law. One of the slaves’ main leaders was François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, also known as Toussaint L’Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda. At first Toussaint allied with the Spaniards in Santo Domingo (the other half of the island of Hispaniola). The rebels became reconciled to French rule following the abolition of slavery in the colony in 1793, prompting Toussaint to switch sides to France. For some time, the island was quiet under Napoleonic rule. On 1 July 1801 Toussaint promulgated a Constitution, officially establishing his authority as governor general “for life” over the entire island of Hispaniola. Article 3 of his constitution states: “There cannot exist slaves [in Saint-Domingue], servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French.”. During this time, Napoleon met with refugee planters. They urged the restoration of slavery in Saint-Domingue, claiming it was essential to their profits.

Jefferson supplied Toussaint with arms, munitions and food. He was seen as the first line of defense against the French. He had already foreseen that Toussaint would put up considerable resistance, and anticipated on Napoleon’s failure in the West-Indies. It would prove to be one of the most important strategic choices in the development of the current United States.

On 25 March 1802 Napoleon signed the Treaty of Amiens. It turned out not be be more than a truce. The Treaty gave both sides a pause to reorganize. In 18 May 1803 the war was formally resumed. During this peace Napoleon made reestablishing France’s control over its colonial possessions a priority. In December 1801 he sent Charles-Victor-Emmanuel Leclerc (1772-1802) to the colony.

Meanwhile Toussaint enforced a hard regime on plantation laborers. By crushing a rebellion of the workers, he isolated himself and weakened his position. Leclerc landed at Cap-Français in February 1802 with warships and 40,000 soldiers. The French won several victories and after three months of heavy fighting regained control over the island. The revolutionary generals led a fanatic guerrilla war against the French troops and in a number of occasions were very successful. However, Toussaint faced a major setback when some of his generals joined Leclerc. Toussaint’s mixed strategies of total war and negotiation confused his generals who one after the other capitulated to Leclerc, beginning with Christophe. Finally Toussaint and later Dessalines surrendered.

Toussaint was forced to negotiate a peace. In May 1802 he was invited by the French general Jean Baptiste Brunet for a negotiation. His safety was guaranteed. On Napoleon’s secret orders Toussaint was immediately arrested and put on ship to France. He died in a prison cell in the French Alps of cold and hunger. It should be mentioned that Dessalines played a significant role in the arrest of Toussaint (Girard). Dessalines obtained 4000 francs and gifts in wine and liquor for him, his spouse and the officers involved (Girard). When in October 1802 it became apparent that the French intended to re-establish slavery, because they had done so on Guadeloupe, Toussaint’s former military allies, including Jean Jacques Dessalines, Alexandre Pétion and Henri Christophe, switched sides again and fought against the French. In the meanwhile disease took its toll on the French soldiers. The revolution was revitalized when Leclerc died of yellow fever in november 1802. The Haitian Revolution continued under the leadership of Dessalines, Pétion and Christophe.

After the death of Leclerc, Napoleon appointed the vicomte de Rochambeau (who fought with his father under George Washington in the American Revolutionary War) as Leclerc’s successor. His brutal racial warfare drove even more revolutionary leaders back to the rebel armies.

The revolutionary ideas spread

The situation in the Caribbean was chaotic. The situation in Europe was the direct cause, but the Haitian revolution contributed to uncertainty as well, as illustrated by events that took place on the neighbouring island of Curaçao.

In September 1799, two French agents from Saint-Domingue, together with a Curaçao-resident French merchant, Jean Baptiste Tierce Cadet, were arrested for conspiring to overthrow Curaçao’s government and to liberate the slaves. They were deported without trial. Tierce Cadet was accused of being the local ringleader. He was accused of being part of a plan originating in Saint-Domingue: the liberation of the slaves in all the colonies in the Caribbean. Eight months after being deported from Curaçao, Tierce, en route to France, arrived in the Batavian Republic. He was travelling with an officer of the Batavian navy, Jan Hendrik Quast. Both men were arrested and questioned. The Batavian authorities intended to put Tierce on trial for trying for overthrowing the Curaçao government and plotting to liberate the slaves. However, it appeared very difficult to produce the necessary evidence against him.

Klooster, 148-149

Saint-Domingue becomes independent

The Battle of Vertières on 18 November 1803 was the final event that stood between slavery liberty in Saint-Domingue. It involved forces made up of former enslaved people on the one hand, and Napoleon’s French expeditionary forces on the other hand. Vertières is situated in the north-east, near the sea. By the end of October 1803, the revolutionary forces fighting the expeditionary troops were already in control over most of the island.

The revolutionary troops attacked the remaining French soldiers at Vertières. After heavy fighting the battle ended when heavy rain with thunder and lightning drenched the battlefield. Under cover of the storm, Rochambeau pulled back from Vertières. At the Surrender of Cap Français, Rochambeau was forced to surrender to the English. He was to taken England as a prisoner on parole, where he remained interned for almost nine years.

Although the fighting in Saint-Domingue during the time of the revolution had horrible moments and both parties committed gruesome war crimes, one particular event in the battle of could be seen as a sign of respect by Rochambeau towards the revolutionaries.

At 4 a.m. on Nov. 18, 1803, part of the forces began an attack on Breda, one of the outlying forts. Rochambeau surprised, left Cap and took a position with his honor guard on the entrenchments at the fort of Vertieres, between Breda and Cap. To take the objective specifically assigned to him, François Capois and his troops had to cross a bridge that was dominated by the fort at Vertières.

Burton Sellers

Capois, on horseback, and his men met a hail of fire as they advanced. Despite a bullet passing through his cap, Capois urged his men forward. Even a bullet which leveled his horse and another which again passed through his cap did not stop Capois from flourishing his saber and leading his men onward with his continuing cry of Forward! Observing this, Rochambeau’s guards applauded. Rochambeau caused the firing to be stopped and sent a hussar forward with compliments for Capois! Then the battle recommenced.

Shortly after the battle, the first declaration of independence was read in Fort-Dauphin on 29 November 1803. It was signed by Dessalines, Christophe and Clerveaux. They all had been generals under Leclerc little more than a year earlier. The declaration did not mention the current name “Haiti”, but still spoke of “Saint-Domingue”. The second Act of Independence was read by Dessalines on the Place d’Armes of Gonaïves on 1 January 1804. The act marked the beginning of independence what from that moment on would be known as the republic of Haiti. It marked the beginning of the end of slavery in the colonies.

Napoleon’s Legacy

Because Napoleon had failed to re-enslave Saint-Domingue he was missing the plantation revenues. As war with England was inevitable and he could not raise enough assets, Napoleon abandoned his colonial policy. France’ immense territory of Louisiana was sold to the United States on 30 April 1803 by means of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty. It was the birth of what now is considered the most powerful nation in the world, as Livingston made clear in his famous statement: “We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives…From this day the United States take their place among the powers of the first rank.”

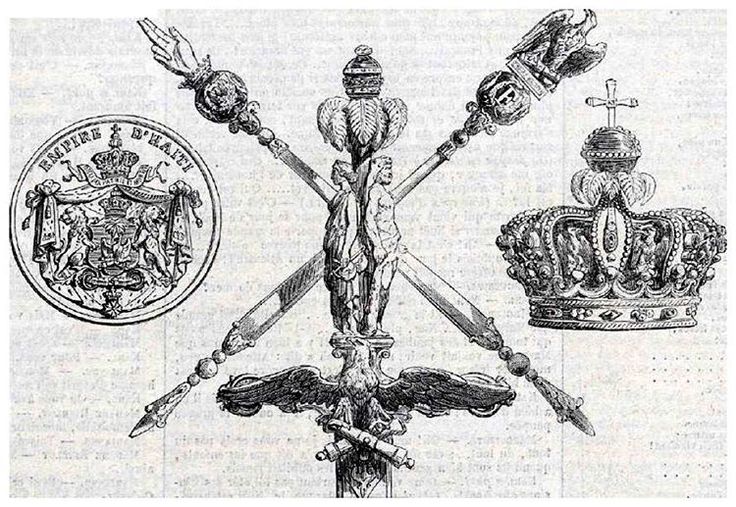

After the declaration of independence, Dessalines proclaimed himself Governor-General-for-life of Haiti. Between February and April 1804 he orchestrated the massacre of the white Haitian minority; between 3,000 and 5,000 people. On 2 September 1804, Dessaline proclaimed himself emperor under the name Jacques I of Haiti. He was crowned on 8 October 1804 (two months before Napoleon) with his wife Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité at the Church of Champ-de-Mars, Le Cap by Pere Corneille Brelle, later His Grace Monseigneur the Archbishop of Haiti, Duke de l’Anse, and Grand Almoner to King Henry I. Jaques I Promulgated the Constitution of Haiti on 20 May 1805 (Buyers: 2017).

Former revolutionary Henry Christophe succeeded Emperor Jacques I I as provisional Head of State after his death on 17 October 1806. He was installed as Lord President and Generalissimo of the Land and Sea Forces of the State of Haiti with the style of His Serene Highness on 17 February 1807. Christophe was proclaimed as King of Haiti and assumed the style of His Majesty on 26 March 1811. He was Crowned by His Grace Monseigneur Corneille Brelle, Duke de l’Anse, Grand Almoner to the King and Archbishop of Haiti, at the Church of Champ-de-Mars, Le Cap-Henry, on 2 June 1811. Christophe was Grand Master and Founder of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Henry on 20 April 1811. He married at Cap Français on 15 July 1793, H.M. Queen Marie-Louise (b. at Bredou, Ouanaminthe on 8 May 1778; d. at Pisa, Italy, on 14 March 1851, bur. there at the Convent of the Capuchins). Christophe committed suicide at the Palace of Sans-Souci, Milot, on 8 October 1820, having had issue, three sons and two daughters. He was succeeded by another revolutionary general, Alexandre Sabès Pétion, who had as well been one of Haiti’s founding fathers (Buyers: 2017).

In 1825, France demanded Haiti compensate France for its loss of slaves and its slave colony. It threatened with a new invasion. In 1838, France agreed to a reduced amount of 90 million francs to be paid over a period of 30 years. In 1893 the final part of the principal was paid. By 1947 Haiti paid the modern equivalent of USD 21 billion (including interest) to France and American banks as “compensation” for being enslaved for centuries.

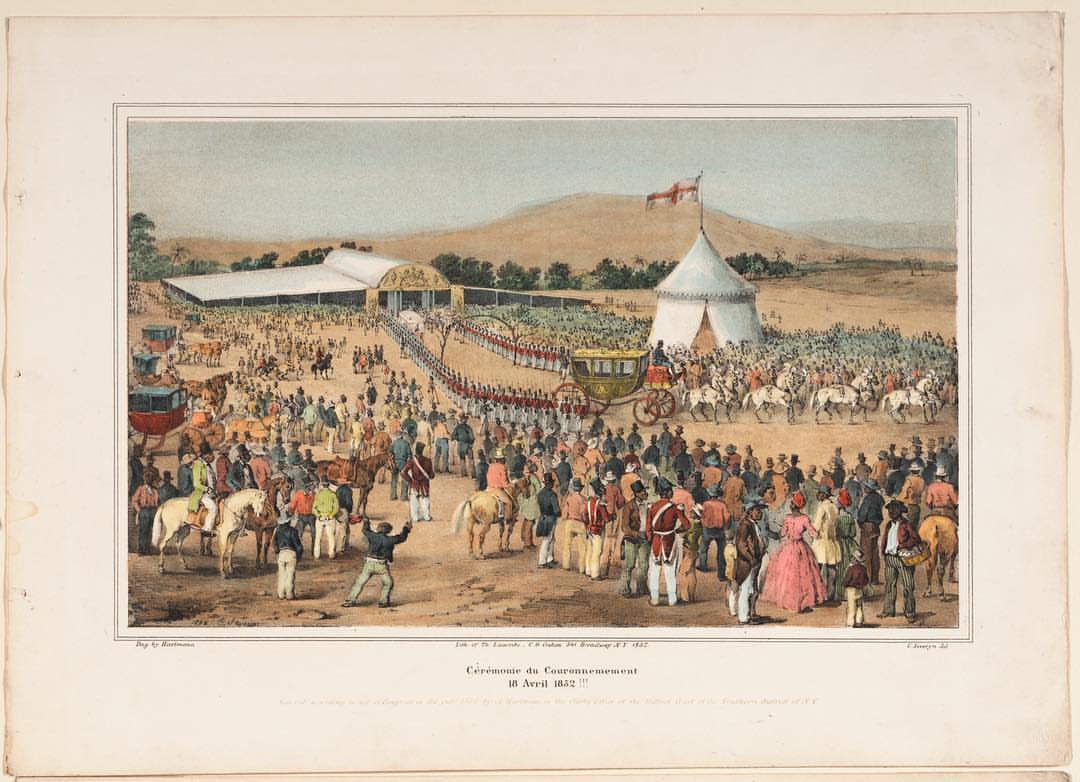

In 1849 the Napoleonic style was copied by Emperor Faustin I of Haiti who adopted the style of His Imperial Majesty. Faustin I was proclaimed emperor at the National Palace, Port-au-Prince, on 26 August 1849 and crowned at the renamed Imperial Palace on the same day. He was consecrated at the old Cathedral of Notre Dame de l’Assomption, Port-au-Prince, on 2 September 1849. The emperor promulgated a new Constitution on 20 September 1849 and was crowned at the Champ de Mars, Port-au-Prince, in the presence of the Vicar-General Monsignor Cessens according to Episcopalian (Franc-Catholique) rites, on 18 April 1852. Faustin was styled Chief Sovereign, Grand Master and Founder of the Imperial and Military Order of St Faustin and the Imperial Civil Order of the Legion of Honour 21 September 1849, and of the united Orders of Saint Mary Magdalen and Saint Anne 31 March 1856, all in three classes. Grand Protector of the Franc-Masonic Order 1850-1859. Patron Collège Faustin 1848-1859. He was founder of the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1856 (Buyers: 2017).

Literature

Alaux, Gustave D., Maxime Raybaud, and John H. Parkhill. Soulouque and his empire. From the French of Gustave dAlaux. Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1861.

Burnard, Trevor G., and John D. Garrigus. The plantation machine: Atlantic capitalism in French Saint-Domingue and British Jamaica. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Burton Sellers, W.F. “Heroes of Haiti.” Windows on Haiti: Heroes of Haiti. Accessed July 08, 2017. http://windowsonhaiti.com/windowsonhaiti/heroes.shtml.

Buyers, C. “HAITI – Royal Ark.” Accessed July 8, 2017. http://www.royalark.net/Haiti/haiti6.htm. Website by Christopher Buyers on the genealogies of the Royal and ruling houses of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas.

Cases, Emmanuel-Auguste-Dieudonné Las. Memorial de Sainte Hélène. Journal of the private life and conversations of the Emperor Napoleon at Saint Helena. Boston: Wells & Lilly, 1823.

Christophe, Henri, Thomas Clarkson, Earl Leslie Griggs, and Clifford H. Prator. Henry Christophe, a correspondence. New York: Greenwood Press, 1968.

Dwyer, Philip. Napoleon: the path to power, 1769 – 1799. London: Bloomsbury, 2008.

Dwyer, Philip G. Citizen emperor: Napoleon in power. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Girard, Philippe R. Slaves who defeated napoleon: toussaint louverture and the haitian war of independence, 1801-1804. Tuscaloosa: Univ Of Alabama Press, 2014.

Klooster, Wim, and Gert Oostindie. Curaçao in the age of revolutions, 1795-1800. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Klein, Herbert S. The Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

“The Louverture Project.” Accessed July 08, 2017. http://thelouvertureproject.org. The Louverture Project (TLP) collects and promotes knowledge, analysis, and understanding of the Haitian revolution of 1791–1804.

Mentor, Gaétan. Dessalines: le̕sclave devenu empereur. Pétionville, Haïti: Impr. Le Natal, 2003.

Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon: a life. New York: Penguin, 2015.

Sloane, W. M. “Napoleons Plans for a Colonial System.” The American Historical Review 4, no. 3 (1899): 439.

Sortais, Georges. Important tableau par Louis David: “Le sacre de Napoléon”. S.l.: S.n., 1898.