Since defeating the imperial armies of Britain, France, and Spain during the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), Haiti has been struggling to achieve recognition of its right to sovereignty. In Britain, Haiti has been perceived as lacking an appropriate and capable government ever since Jacques Dessalines declared independence in 1804, a view that persisted throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as racism proliferated in step with expanding empire. Recent media reports concerning Hurricane Matthew and the country’s presidential elections show that even today Haiti continues to face a geopolitical system in which its rights as a sovereign nation are routinely ignored.

Haiti in Imperial Britain

Throughout the nineteenth century, Haitian leaders made every effort to assert their independence, and the Album Impériale d’Haïti (1852) commissioned by Emperor Faustin Soulouque provides one key example. This set of pictures presents an image of a Haitian government that is equal to any European counterpart, with characters depicted proudly facing the viewer. The Haitian Emperor is dressed in identical clothing to that of Napoleon I during the latter’s coronation in 1805, making a clear statement of the right to rule. The Album did not, though, have the desired effect: it was received in Britain not as evidence that Haitian sovereignty was to be respected, but rather that Haiti acted mainly in relation to the French sphere of influence and parodied its political institutions.

As one writer opined in the Morning Chronicle:

When Napoleon made himself absolute master of France, his example was followed by Dessalines, the dictator of Hayti. But in our time the barbarous nation set the example — Soulouque declared himself Emperor of Domingo [Haiti]; and it was not until that vigorous step had been taken by the coal black Sovereign of Hayti, that Louis Napoleon ventured to make his attempt.[1]

In this instance, statements of Haitian independence were reinterpreted to critique Britain’s old imperial rival, France. Remonstrations from Haitians, meanwhile, went unheard.

Haiti’s perceived position outside of empire became increasingly problematic for people in Britain as imperial culture became more entrenched. As Jan Pieterse argues in the case of images of Africans in this period, Haitians were increasingly represented as the ‘enemy’.

In Haiti, the centenary of Haitian independence (1904) was celebrated in the country with horse races, public speeches, and fireworks, while the capital was adorned with national flags. The President, Nord Alexis, was keen to use the event to unite the country behind his political party. For British onlookers, including the Consul General, A. G Vansittart, the reminder of events in Haiti leading up to the Declaration of Independence (which decimated European armies) was terrifying.

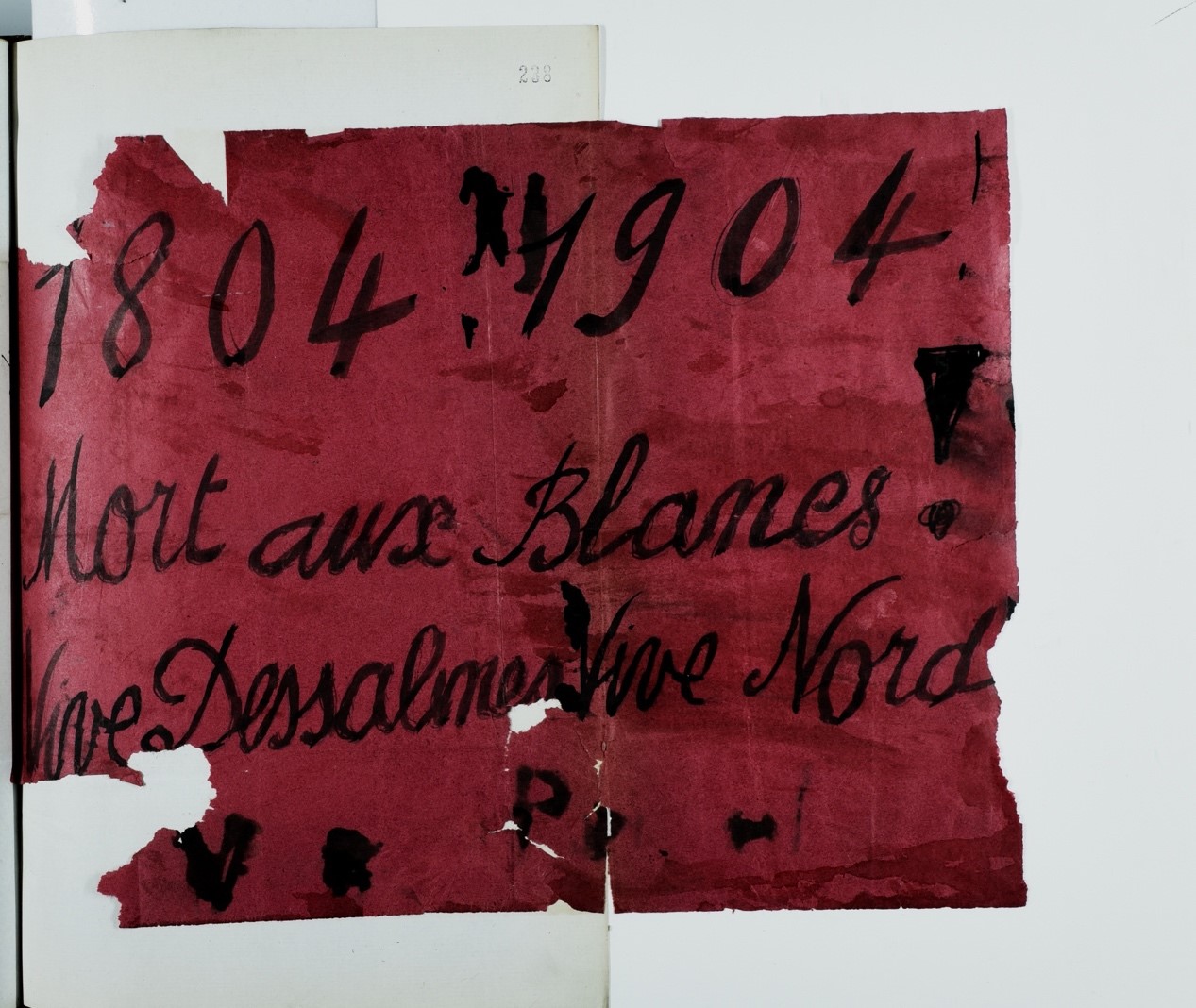

Throughout 1904, Vansittart relayed his anxieties about the Haitian threat to the lives and prospects of British people. In May, Vansittart requested that a warship be put on standby, complaining that ‘a massacre of white residents is now quite within the bounds of possibility… at the first sign of such a catastrophe, if the telegraph wires are not cut, I shall telegraph to Your Lordship for protection.’[2] Along with his messages, the Consul sent examples of placards found in the street, as evidence of the threat to the lives of foreigners.

Figure 3: Placard sent from Vansittart to the Foreign Office. Reads “Death to the whites [foreigners]! Long live Deassalines, long live Nord!” Vansittart to Lansdwone, 19 December 1903, FO 35/179, p. 238.

No massacre ensued but Haitian independence was reported as a crisis that could require foreign intervention, clearly contradicting Haiti’s efforts to achieve a sincere recognition of sovereignty.

Over the course of the nineteenth century such struggles over the definition of the significance of Haitian independence continued. For Haitian leaders it was of the utmost importance that imperial powers across the Atlantic World should recognise the Haitian state as sovereign. But the various strategies of denigration employed by people in ‘the West’ suggest that the Haitian government was rarely, if ever, considered legitimate in Europe and North America. This view of Haiti came with constant military threats, initially in the form of gunboat diplomacy, and then with the invasion of Haiti by the United States in 1915. The view that Haiti was like an orphan, lacking a paternal influence, converged with the notion that Haitians were inherently unable to enact statehood both to undermine claims for sovereignty and to justify US intervention.

Representing Haiti in 2016: Disaster and Intervention

The idea of Haiti as a natural target for foreign intervention has been repeated in recent media reports concerning both Hurricane Matthew (October 2016) and recent elections (November 2016). In the wake of the hurricane, The Times interviewed a member of Unicef on the spread of cholera, detailing how floodwater mingled with sewage ‘and human and animal corpses, turning streets into breeding grounds for the disease’.[3] Rather than emphasising the role of international forces in introducing cholera to Haiti – a fact only admitted to by the UN after six years of denial – the epidemic was cast as a problem accentuated by the Haitian population: ‘Amid the devastation, desperate residents in one community tried to ambush the trucks carrying food, water and sanitation supplies that have begun to roll into some of the areas worst hit… “Misery, misery… Hunger is killing us”, they chanted.’[4]In subsequent reports, The Times consistently neglected to interview Haitians on their experiences during the hurricane. Instead, it maintained a narrative in which international forces such as the UN and Unicef were attempting to resolve the crisis, while Haitians were described either as passive aid recipients or as feckless amplifiers of the crisis. Once again Haiti became a place incapable of ‘proper’ statehood and in need of Western supervision.

The Times was joined in its representation of Haiti by the Guardian in its reporting on presidential elections at the end of November. It focused on the violence following the elections and emphasised claims of corruption: ‘Violent protests have erupted in Haiti… Police used teargas on protesters in the La Saline neighbourhood… [They] called the results an “electoral coup”.[5] The Guardian’s chosen sources were the US Embassy and a Reuters journalist who could say little more than that they had ‘overheard gunshots’. Considered within a history of Western ideas about Haiti, these media reports reinforce a narrative of Haiti as incapable of proper government, lacking as they do protection from natural disasters and from themselves. Such ideas have been central to aggressive acts of intervention by imperial powers in Haiti. Critically, this image of Haitians has relied on a refusal to incorporate Haitian voices into narratives about their own country. This happened throughout the nineteenth century, when Haiti was depicted as a pariah state and a warning against decolonisation, and it continues today. To deepen understanding of Haiti and to provide more appropriate assistance in the wake of natural disasters Western organisations and Western media need to enter into dialogue with Haitian people and seek the opinions of Haitians themselves.

Conclusion

The significance of Haiti in Britain, however, has not only been defined by imperial and neo-imperial powers. Haiti’s radical act of decolonisation, as perceived through its revolution and the maintenance of a tenuous independence until 1915, and then from 1934 onwards, has served as a multifaceted example of liberation from colonialism. As Colin Clarke found during his research in Jamaica as the country moved towards independence, for advocates of radical decolonisation Haiti could variously mean the ‘butchering of whites’, the promise of an independent state under the control of a black population, or indeed a warning against extreme isolationism. These alternative ideas about Haiti and radical decolonisation rested on a staunch recognition of the right to Haitian sovereignty, and as Caribbean peoples moved around the Atlantic and entered Britain, they began to render British ideas about Haiti multiple and contradictory. But what is clear is that the Dessalines’ declaration of independence in 1804 was only the start of Haiti’s struggle for self-determination in the Atlantic World.

Notes

[1] [Anonymous], ‘The Imperial Precedents’, Morning Chronicle, 29 November 1852, p. 4.

[2] A. G.Vansittart to Marquis of Lansdowne, 11 May 1904, FO 35/180, p. 110.

[3] ‘Cholera Hits in Haiti in Hurricane’s Wake’, The Times, 10 October 2016, p. 23.

[4] ‘Choler Hits’.

[5] ‘Haiti: Violent Protests Erupt Over Presidential Election Result’, Guardian, 29 November, 2016, online edition.